|

| Things artists all too often take for granted. |

|

Paint Torch, Claes Oldenberg,

Lenfest Plaza, Philadelphia,

a brush not to be taken

for granted. |

Many artists, myself included sometimes, would rather do art than learn about art. That goes for everything from color mixing to blending and paint strokes. Having taught art for so many years I'm a great believer in learning by doing. That's how I did it, and I'm rather partial to thinking that's the best way as well. In general, most artists would rather learn how to paint than the academics involved. Because of this pen-chant, we often take for granted many of the items we use to accomplish this learning, and eventually in producing art. That is, until we go to buy them, then take a look at their price tags. Does the word "geesh" come the mind? It's only when we come face to face with sticker shock that we begin to learn something about art. We learn the difference between student and professional grade colors, for instance. And we find ourselves pondering whether to invest in the best brushes, the cheapest brushes, or the merely good-enough-for-now price range. As with most things in life, you get what you pay for. But still, the question lingers, why do brushes cost so damned much?

|

| Brushes, Julia Swartz, probably painted with "brights." |

There are two basic mindsets when it comes to buying artists' brushes. Do you buy top-of-the-line and take on the persistent onus of their perpetual care and cleaning, or do you buy the cheap stuff, use them till their useless, then toss them? There is a middle ground but that need not be discussed in that it obviously involves both mindsets depending upon the artist's state of mind after a painting session. Beyond that, there are so many things to learn about brushes I'm almost reluctant to delve into details. But, as with search filters in a browser, a few basic decisions immediately limit the complexities. The first has to do with media--oil, acrylics, or watercolor? Today, each have their own type of brushes especially made to facilitate and enhance their medium. Watercolor brushes tend to be soft, flexible, sable; oils tend toward stiff bristles, while acrylic colors, being synthetic, prefer synthetic bristles somewhere between the first two as to their feel. There, that was simple enough, right?

|

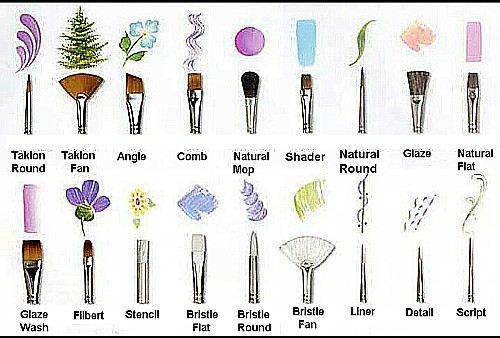

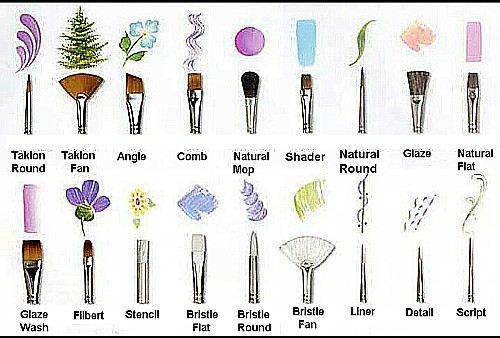

| The top row displays watercolor brushes. The bottom row apply to oils and acrylics. I like this chart because it involves different strokes for each type. |

|

Old brushes are now referred to as

"vintage." |

Now, despite the simpli-fication, things get compli-cated. In all three major media, brushes have been designed and developed for specific effects, not to mention painting styles. The chart above helps differ-entiate among them. The artist painting in a highly detailed, realist manner will prefer brushes with longer hairs or bris-tles. Artists involved in impression-ism or Expressionism will usually prefer shorter lengths, often refer-red to as brights. Keep in mind here, I'm speaking in generalities, not absolutes--tastes vary.

As all artists realize, each type of brush mentioned above comes in as many as a dozen different sizes. The choice depends upon the size of the paintings being produced as well as the artists style and method of applying paint. I have always noticed a tendency for beginning artists to choose a brush smaller than they should in an attempt to exercise more control over the paint while in general, the rule is to use as large a brush as possible so as to obtain a looser, more spontaneous, more painterly application of paint as seen in Julia Swartz's

Brushes. The painting of the vintage brushes (above) demonstrates a tighter, more refined approached painted with smaller brushes.

|

| Cave painting tools--crude, but effective, especially in the right hands. |

|

Another set of Paleolithic

painting possibilities. |

Perhaps no other element of the painting process, not even the paint itself, has undergone greater development that the lowly paint brush. Although we don't know precisely what artists of the Paleolithic Era used to decorate their walls, archae-ologists and art experts have put their heads together and come up with a number of possibilities (above and left). The Egyptian brushes (below) from several thousand years later show little improvement, though they appear to be more "manufactured" rather than hand-made. I've got some that look a little like these. I use them only when I'm painting

Egyptian scenes.

|

Egyptian brushes from around 1500 BC.

(Nothing a little turpentine wouldn't help.) |

Brushes from the Italian Renaissance (below) were some of the first made by professional brush makers rather than the artists themselves. I'm sure the ones seen below have been well-used and misused over the centuries, but one still has to marvel that artist such as Leonardo, Michelangelo, Raphael, Titian and Tintoretto could turn out such masterpieces with such relatively crude tools. Even artists' brushes from as recently as the 1800s (bottom) bear some remarkable differences from what we know now. I wonder at what point manufacturers quit making handles that looked like Victorian bedposts?

|

| It's not the brush but the hand guiding it that makes the difference. |

|

19th-century painting tools. There was little

standardization or specializing at the time. |

|

| Don't you wish you were ambidextrous? |

Hello! I loved your text, and also thought it was very insightful! Thanks!

ReplyDeleteDaniel--

ReplyDeleteThanks. I love it when people take the time to read and enjoy my "insightful" texts. I just reread it myself. Wish all my texts could be so insightful. :-)