|

| Heston's Michelangelo was no Ben-Hur with paint on his face. |

|

| In some ways, Stone's The Agony and the Ecstasy is better than Lust for Life. |

Irving Stone's historical novel, The Agony and the Ecstasy, coming on the heels of his biographical A Lust for Life, should have been a much better movie that it was. That's not to say it was a bad film adaption of the turbulent relationship between Michelangelo Buonarroti and Pope Julius II (Giul-iano della Rovere). It had many of the important elements of a great movie. The book was a bon-afide best-seller. The film was blessed with familiar characters, a great historic event, good direction, and adequate (if not outstanding) performances by it's leading actors, Charlton Heston (as Mich-elangelo) and Rex Harrison (as Julius). According to the critics, the one thing it lacked was a good script. The film was variously described as "wordy," "an illustrated lecture," and "heavy on the dialog, light on the action"). Such criticism seems strange in that Julius II was nicked-named "the warrior pope," and Michelangelo was nothing if not combative at times. In fact, there are quite a number of medieval combat scenes in the film. Still, it was a movie about art, and art does not easily lend itself to an Ian Fleming action escapade, much less the frantic editing pace of virtually all of today's moviemaking. The Agony and the Ecstasy is thoughtful.

|

| Irving Stone rests on his laurels (top). Director Carol Reed instructs Michelangelo (Heston) in how to paint ceiling frescoes. |

The much-disparaged screenplay was written by Phillip Dunne around 1960, shortly after the book came out. The script was not a strong and soaring drama. When people of my generation claim “they don’t make films like they used to”, The Agony and the Ecstasy is typical of the kind of films they’re referring to. That's not all bad. Director/producer Carol Reed's epic opus is a solid example of a calm, more sedate style of filmmaking that today is all but extinct. Editing is kept to a minimum, the pace is kept slow, which seems design as encouragement by the filmmaker to ignore the plot and just wallow in the scenery. Whether it’s the recreation of 15th century Rome as Michelangelo and the Pope butt heads over the painting of the Sistine Chapel, or long, lingering shots of the painter’s work itself. The film is more involved in sumptuous visuals, rather than telling a compelling story. Nowadays, attention spans are distressingly short. Editing plays a much more prominent role in most mainstream films, while the number of cuts per second has skyrocketed into fifth gear.

|

| Notice, Michelangelo is not even mentioned. |

On the other hand, older films like this are often crushingly boring. Even with a masterful screenplay (which was not the case in this case), it's obvious that there’s barely enough story here to contain a 40-minute documentary, let alone a feature film trying to be some kind of character study. Films aren’t paintings any more (if they ever were). They’ve become something more dynamic, reflecting a society that moves faster and overloads its citizens with information. Every art form should evolve in this manner, to suit the world in which it is made. If it doesn't, it ends up stationary; and people don’t watch such films anymore.

|

| Even with makeup, Heston bore only a passing resemblance to Michelangelo. The painter was in his early thirties when he did the Pope's ceiling. Heston was ten years older when he did the movie. |

There were problems from the beginning. The movie was originally supposed to have been filmed in 1961, directed by Fred Zinnemann and starring Burt Lancaster. But for a variety of reasons, production was delayed for three years. Laurence Olivier, the first choice for Pope Julius II was unavailable. Spencer Tracy was offered the role of the Pope before Rex Harrison was cast. When it came time to film the feature, the Vatican balked at using the real Sistine Chapel so it had to be recreated on a sound stage at Cinecittà Studios in Rome. During the production, Rex Harrison and Charlton Heston developed a intense dislike for one another. So much for chemistry.

|

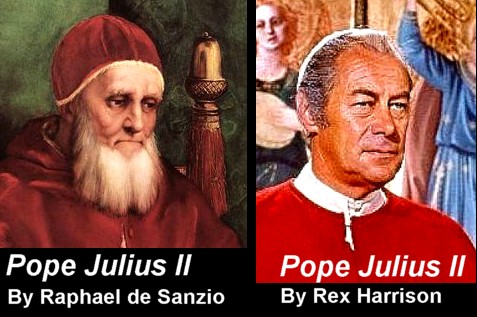

| If Heston bore little resemblance to Michelangelo, Rex Harrison looked nothing at all like Julius II. |

Although I tend to love any film with Rex Harrison, as an actor he bears the burden of many others in his profession. He can never seem to rise above his own persona. Whether it's Pope Julius, Julius Caesar, or Henry Higgins, we always see Rex Harrison playing his role, rather than becoming his character. Moreover The Agony and the Ecstasy was burdened with quite a number of historically inaccurate details while its historic figures such as Donato Bramante and Raphael were undifferentiated from Stone's fictional ones, mostly the de Medici clan. Michelangelo was depicted lying on his back atop his scaffolding as he painted. In reality, he stood up and, in essence, bent over backwards. And although the artist is shown working with two or three assistants, their importance is greatly minimized.

|

| Bramante was the primary architect for St. Peter's Basilica. Contessina de' Medici was a fictional character. |

Lovely as she was, Diane Cilento as Contessina de' Medici was invented by Stone as a token female presence in Michelangelo's tortured existence. Her name was simply plucked from the de' Medici family tree, (as was that of her "brother," Giovanni, in the film). It's quite probable she also endured a sex change in that most of the de Medici offspring about Michelangelo's age were male. Her chiding, though sympathetic, role in the film was likely set to preclude any possible suggestion that Michelangelo was gay. In 1965, that would have meant disaster.

The Agony and the Ecstasy, for all its shortcomings, did have its "moments." The thought provoking discussions between the painter and the pope regarding the nature of God were fascinating, as was the humorous political divide among the church cardinals as to whether the pope's chapel should have naked figures writhing all over its ceiling. Yet, unlike Lust for Life and several other films about the lives of artist, this one actually turned a modest profit. Boasting an $7-million budget the film has grossed about eight million. At the 1965 Academy Awards, though nominated for five, the film won none. It fared no better at the Golden Globes where Rex Harrison was nominated as Best Actor and (amazingly) Phillip Dunne for Best Screenplay. Neither won.

|

| How to paint a ceiling in 138 minutes. |

|

| Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel. He even designed the uniforms seen here for the pope's Swiss Guards. |

No comments:

Post a Comment