|

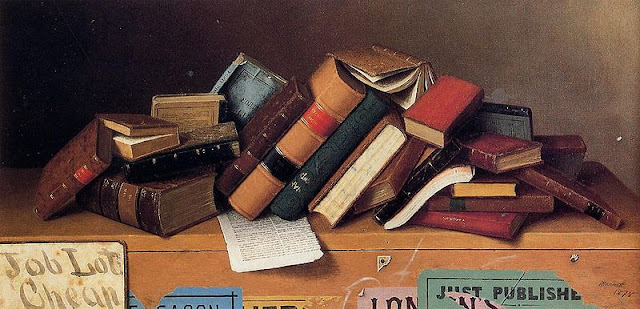

| Job Lot Cheap, 1878, William M. Harnett |

|

| William M. Harnett |

|

| Job Lot Cheap, 1892, Frederick Peto. Harnett and Peto were close friends but that didn't keep them from competing, each trying to out-paint the other. |

William Harnett, born in Ireland in 1848, may have been one of the first still-life painters to realize this "shallow" factor. Having been born during the Irish potato famine, he was fortunate that his family could afford to emigrate to the United States. Harnett became a U.S. citizen shortly after the Civil War and made a living as an engraver of fine silver dinnerware, while studying art at night school, first in his hometown of Philadelphia, later in New York at the Cooper Union and the National Academy of Design. His earliest paintings date from the mid 1870s. Job Lot Cheap (top) is one of his earlier works, displaying two of the most noticeable attributes of Harnett's work, his still-lifes appear not to be deliberately "arranged" (even somewhat disarranged), and they depict very common, everyday objects the viewers would likely confront daily, yet without seeing them as apt subjects for an artist. (His friend, Frederick Peto painted his version with the same title, above, a few years later in a sort of running competition between the two men that lasted most of their lives.)

.jpg) |

| Vanitas - Still-life, 1625, Pieter Claesz--contrived and by no means common objects. |

Harnett was by no means the first artist to try to "fool the eye." The early American painter, Raphaelle Peale, had been most notably successful in the U.S. while Dutch painters such as Evert van Aelst, Pieter Claesz (above), Floris van Dyck, Christian Berentz, Floris van Schooten, and Jan Jansz Treck not only invented the genre but lifted it to high art in the rarified world of 17th century Dutch painting. What Harnett did, aside from continuing to popularize this type of work here, was to realize the importance of the shallow depth of field in enhancing the tromp l'oel illusion of reality. Beyond that, he did so many of them, to the exclusion of virtually any other type of work, that he became quite good at what he did. He didn't even leave us a self-portrait.

|

| 1883 1884 1885 After the Hunt, 1883-85, William M. Harnett. (The differences in coloration is largely photographic.) |

|

| After the Hunt, 1885, William M. Harnett the oddball in the series. |

No comments:

Post a Comment